My novel, The Fortress at the End of Time, is about a betrayal. It is not a secret or a twist or a surprise. In fact, it is revealed within the first few paragraphs. I am in the habit of writing betrayals or twists in this fashion because I feel that, too often, books are not an ideal form for a sudden or unexpected twist. The format does not, to me, create an ideal space for a sudden reversal similar to what we see on screen. Even on screen, twists are generally more about the big reveal, itself, than whatever that thing revealed may or may not symbolize or indicate to the larger purpose of the narrative. The momentum of the story, and the meaning of the story, is moving in a direction, after all. A sudden shift in the flow is jarring, and breaks the wall of narrative expectations. Attention span is so fragile, and books are so easy to put down. They require a level of concentration that no other artistic medium I know demands.

The jarring aspect is why, I feel, video games are a better place for this technique (when used sparingly!). Some of my favorite dusty, musty old video games contain a sudden twist that breaks the narrative flow just so. The hypnosis of gaming, the repetitive acts and actions, leads gamers into a sort of haze of muscle memory. When betrayal comes, a twist of the plot—again, only if well done—breaks the momentum of the narrative and forces the player to think about events in the game, and the actions they’ve been virtually doing. It works because the player is part of the narrative, not distant from it.

Some of my favorite moments in games—old, old games that you youngsters might not even recognize—involve a sudden twist or reversal, and some of the worst moments in video game storytelling also involve these. Here are five examples of the sudden betrayal, good, bad, and really well done.

(Beware: here there be spoilers, but all the games are ancient!)

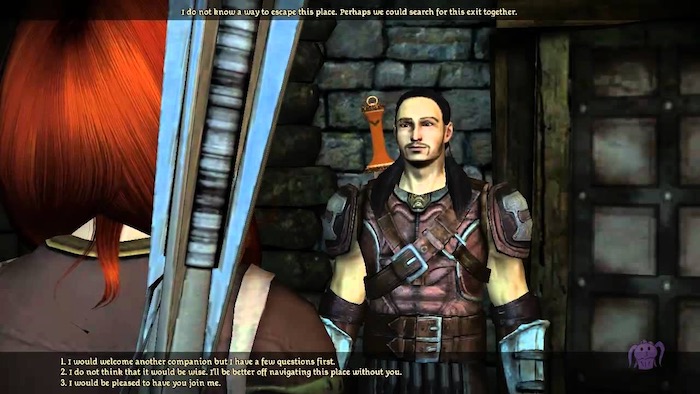

Yoshimo’s Betrayal

In Baldur’s Gate 2: The Shadows of Amn, arguably the War and Peace of the Infiniti Engine RPGs, there is (finally) an Asian-themed character. He is a plucky, nimble, daring thief and bounty hunter that the player encounters early in the game, while escaping Irenicus’ dungeon. He is friendly, helpful, and a valuable asset to the party for much of the early game. Then, despite your friendship, he reveals his treachery in Act 3. All along, he had been a plant for Irenicus, sworn to serve the evil wizard through a magical geas of compulsion. All that epic equipment and skill the player had invested in him turns against the player. Ultimately, the player must kill a friend, who had no choice but to fight to the death. Evil wizards are the worst.

Overlord’s Ending

Rhianna Pratchett was the game writer on this amusing little interpretation of Pikmen that went on to become a series. It was well-written, full of tongue-in-cheek fantasy tropes, and warped humor with the aggressive and loyal little goblins that minion with gusto for their Overlord. Over the course of the game, the player is encouraged by the narrator and mentor figure to do nefarious acts of evil, and to encourage the minions to do the same. The player can choose to be a “good” overlord of the land, and use their power to help. The big reveal ties into this mechanic, and the larger narrative, when, in the end, the player discovers that he was once actually a hero going after an evil sorcerer who got a bonk on the head. The minions, in their craving for evil leadership, placed the amnesiac hero in charge, in part, by the urging of the nearly-dead sorcerer. The player had been working for the sorcerer all along! It works well because it connects the layer of the larger narrative of the game to the moment-to-moment gameplay experience over the whole course of the game. Everything comes together into a fulfilling narrative conclusion. Okay, you can see it coming a mile away, but that’s still a good thing. It’s better to not try too hard to make a big twist, and to telegraph it ahead of time, so it is just the right amount of jarring to the narrative.

Aeris’ Death

Creators of Final Fantasy talked about wanting to create a more naturalistic sense of death and loss in a game experience. They created this character, and early in the game, she is taken. It is a sudden and jarring moment. I hate it. It feels cheap. The polished video and cut-scenery is a mockery of the stage directions. The player is standing right there, with a hugongousmongous sword, and doesn’t even have the opportunity to move a little while Sephiroth descends. Player control is taken away. The death has no real artistic connection to the larger narrative, except for the stretch of the concept of a dying world. This is how to do twists poorly in games. Narratively, I did like that in a game about violence and war, at least one of the “heroes” died—but the body count should have been much higher. The end should have been Red XIII and Cloud and Yuffie sitting alone in a filthy slum, drinking and smoking and trying not to cry while they talk about all their fallen friends.

Darth Traya’s Master Plan

Knights of the Old Republic 2 is an amazing game. It could have been so much more. It was released before it was ready, and the ending didn’t quite work or make sense. But, leading up to that ending, some of the best narrative in video game happened, and high on the list was the handling of Kreia, aka Darth Traya. The one-handed former Jedi hides her true nature for her own ends. Revan’s former Master, however, is insidious and corrupts all that she touches, even as she proves herself a valuable ally. The excellent writing and voice acting only enhances the experience of befriending a woman we know we cannot trust. And, she is a friend and ally. She saves you, gives good advice, and generally proves her worth on the team. When she reveals herself to be the final member of a Sith Triumvirate, with her own fortress full of dark acolytes, twisting the whole series of events to her own ends, the Jedi Master must storm the ruined world, and face her. It’s an excellent moment ruined by an incomplete game.

Your First Night in Minecraft

Not, strictly speaking, a story game, Minecraft still manages to make my list of excellent betrayals. By now, everyone knows the skeletons and spiders and zombies and creepers are coming. But, when the game is first played, by players who are not deeply immersed in geek culture, the world is bright and beautiful, full of vistas and creatures and trees and rocks. There is no menace, no terror. The sun passes over the sky in peace and abundance. Then, night falls. The world of beauty and peace turns against you, never to be the same. The tone of the game shifts forever.

Top image: Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children (2005)

This article was originally published in January 2017

Joe M. McDermott is best known for the novels Last Dragon, Never Knew Another, and Maze. His work has appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His novel The Fortress at the End of Time is available from Tor.com Publishing. He holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Program. He lives in Texas.

Joe M. McDermott is best known for the novels Last Dragon, Never Knew Another, and Maze. His work has appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His novel The Fortress at the End of Time is available from Tor.com Publishing. He holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Program. He lives in Texas.